Historical Processes: The Daguerreotype

This was the first out of a series of six articles about early photographic processes. First published here.

Imagine a time before photography: no computers to livestream current events, no phones to show your friends what you ate for breakfast last weekend, no albums to preserve the appearance of long-dead relatives. In 1840, the American novelist, poet, and critic Edgar Allan Poe celebrated the invention of photography as “the most important, and perhaps the most extraordinary triumph of modern science.” Judging in terms of visual culture, it is difficult to argue the contrary.

This article marks the first in a series dedicated to exploring the history of photographic technologies. At a time when most photographs exist as fleeting pixels on digital screens, the materiality of early processes has offered respite to a growing number of contemporary artists. The aim of this series is to provide a historical framework for those interested in learning more about the important figures and inventions surrounding early photography.

Photography emerged from a global patchwork of experimentation spanning the early decades of the 19th century. Varying degrees of success and failure can be found in the work of Thomas Wedgwood, Humphry Davy, and William Henry Fox Talbot in Britain; James Wattles in the United States; Eugène Hubert in France; and Hércules Florence in Brazil. Yet it is the tale of Nicéphore Niépce and Louis Daguerre that leads to the first photographic process to reach the the public eye: the daguerreotype.

Unknown, Frederick Douglass, daguerreotype, 1855

Edwin H. Manchester, Edgar Allan Poe, daguerreotype, 1848

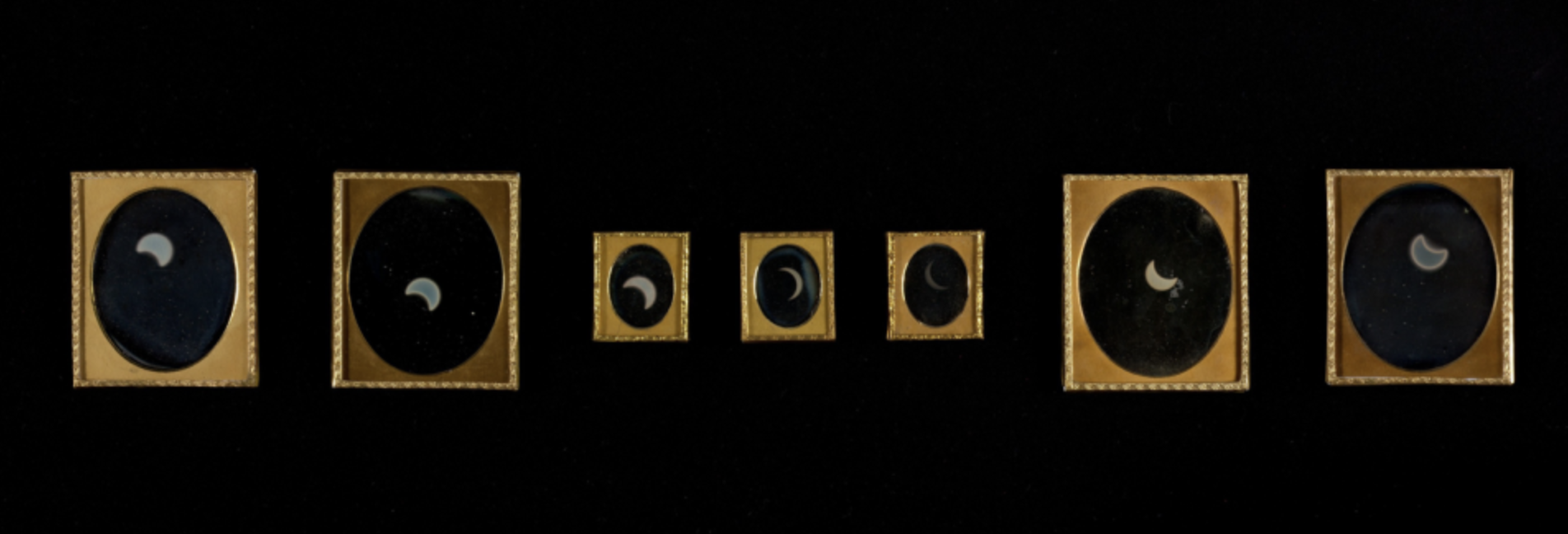

Claudet, Multiple Exposures of the Moon, daguerreotype, 1846–52

The story begins in Chalon-sur-Saône where two ambitious brothers, Nicéphore and Claude Niépce, had invented the first internal combustion engine, the “pyreolophore,” in 1807. Equal parts curious and industrious, the duo’s tinkering ranged from hydraulic pumps to fabric dyes. As the expiration for the pyreolophore’s 10-year patent neared, Claude traveled to Paris and Britain to bolster the invention.

During his time alone, Nicéphore began experimenting with ways of producing photographic images. The optical and chemical technologies underlying early photography had been available for hundreds of years prior to their successful marriage in the 19th century. To produce an image, Niépce turned to the camera obscura, a tool that had been used by artists and draftsmen since the Renaissance. The device relies upon the physical properties of light as it passes through an aperture into a darkened space, forming an inverted image of the scene before it. Its name, “dark room” when translated from Latin, refers to its original form as an architectural structure. In the 17th century, the camera obscura was reduced in scale and modified to reflect its image onto a glass surface for tracing. Paired with a lens to focus the incoming light, it would come to serve as the model upon which cameras would be based to this day.

Nicéphore Niépce

Camera Obscura in its original form

Camera Obscura as a drawing tool

That silver salts darken when exposed to light had been known since the work of the Albertus Magnus in the 13th century. Foreshadowing future developments, Niépce sensitized a sheet of paper with silver salts, and aligned it with the focal plane of a modified camera obscura. Using this method, he was able to create an image on paper, but his success was eclipsed by an inability to stop the reaction. Lacking a way to halt exposure, his images, which he called “retinas,” were fated to ruin when viewed in the light. Seeking a more permanent result, Niépce began exploring the possibility of combining other light-sensitive materials with etching technologies already in use. This ultimately led to bitumen, a substance he was able to render insoluble upon exposure to light.

Nicéphore Niépce, View from the Window at Le Gras, heliograph, 1826

In brief, Niépce’s process involved applying a varnish of bitumen to a copper or tin plate, making an exposure, rinsing the plate in diluted lavender oil to dissolve the unexposed bitumen, and dipping the plate in an acid bath to react with the exposed areas. Multiple prints could then be made from the resulting plate. He named his invention “heliographie,” or “sun-writing.” The moderate sensitivity of bitumen and relatively low amount of light transmitted via the camera obscura made the process best suited for contact printing in direct sunlight. Nevertheless, in 1824, Niépce successfully exposed a bitumen-coated lithographic stone for about five days in a camera obscura, producing his first permanent photographic image using the device. Over the next two years he would successfully use copper and then tin as bases in the camera obscura to produce heliographs. Although technically a success, his process had limited applications due to its technical shortcomings.

Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, daguerreotype, 1844

This is where Louis Daguerre enters the story. Niépce first met Daguerre in Paris, in 1827. An enterprising figure in his own right, Daguerre co-invented the diorama, a popular entertainment venue consisting of elaborately constructed sets and optical illusions designed to impress paying audiences. He avidly employed a camera obscura in his workflow and his access to quality optics proved enticing to Niépce. On the other hand, Daguerre had experimented with preserving images in his camera obscura with nowhere near the success of Niépce. The complementing expertise of the two men would lead to an official partnership in 1829.

By 1832, the pair had invented a new photographic medium: the “physautotype,” a process that used the residue of lavender oil dissolved in alcohol applied to a polished silver plate for reactivity. After the alcohol was evaporated from the plate, it was exposed to light in a camera obscura. Exposure time, while shorter than the heliograph, was still prohibitively long—about eight hours. After exposure, the plate was developed using fumes of white petroleum, producing a direct positive image.

In 1833, Niépce died unexpectedly. The contract signed by the two men stipulated that upon the death of one of the partners, the natural heir of the deceased would succeed him for ten years. Though Niépce’s son Isidore stepped into the partnership, he offered little in the way of advancing his father’s work. Four years later, Daguerre finished the daguerreotype process.

A daguerreotype begins as a sheet of copper, plated with silver. The plate is carefully cleaned with nitric acid, buffed, and polished to reach a mirror-like state. Next, the polished side is exposed to iodine vapor in the dark, rendering it sensitive to light. The plate is exposed in a camera obscura for 3 to 30 minutes depending upon ambient light conditions. Mercury vapor is used to develop the plate and a weak solution of hyposulphite of soda used to fix the image. Despite the permanence of the process, daguerreotypes have extremely delicate surfaces and were housed in specialized cases to protect them from careless handlers and the elements.

Southworth and Hawes, Young Man in Three-piece Suit and Bow Tie, daguerreotype, 1850s

After little luck working out a means of selling his invention by subscription, Daguerre approached François Dominique Arago, the secretary of the French Academy of Sciences. On January 7, 1839, Arago lectured on Daguerre’s process at a meeting of the Academy. On the urging of Arago, the French government awarded Daguerre an annual pension of 6,000 francs and Niépce 4,000 francs to share the invention with the world. Nine months later, on August 19, 1839, the Academy officially revealed the heliograph, physautotype, and daguerreotype processes to the public—although various details of the daguerreotype process had leaked earlier in the year.

Theodore Maurisset, “La Daguerreotypomanie,” 1840

Daguerre’s writing on the daguerreotype began what would become a familiar refrain describing the medium: “[T]he daguerreotype is not merely an instrument which serves to draw Nature; on the contrary it is a chemical and physical process which gives her the power to reproduce herself.” The notion that photography provides access to an unmediated view of the world sparked intense debate over the artistic merits of the new visual form. As “Daguerreotypomania” swept the globe, the art world struggled to reach a consensus on how to receive Daguerre’s invention. Over a century and a half of time has done little to dull the edge of the French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire’s biting remarks on the medium:

“As the photographic industry became the refuge of all failed painters with too little talent, or too lazy to complete their studies, this universal craze not only assumed the air of blind and imbecile infatuation, but took on the aspect of revenge…Can it legitimately be supposed that a people whose eyes get used to accepting the results of a material science as products of the beautiful will not, within a given time, have singularly diminished its capacity for judging and feeling those things that are most ethereal and immaterial?”

Despite Baudelaire’s anxieties about the medium’s encroachment on the transcendent experience he attributes to Art, it was the documentary ability of the daguerreotype that made it most popular. Portraiture and travel views comprised the most frequent uses of the medium.

Rufus Anson, Dog Posing for Portrait in Photographer's Studio Chair, daguerreotype, c. 1855

Baron Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gros, The Salon of Baron Gros, daguerreotype, 1850-7

Daguerre’s original procedure, which required an exposure of “three to thirty minutes at the most,” was ill-suited for making sharp portraits. Luckily, once the daguerreotype’s process was publicly known, optical and chemical refinements were made that alleviated this problem. The British chemist J.F. Goddard first published on the benefits of adding bromine to the iodine used during the sensitization process, boosting the speed of the plates. In 1840, the Hungarian mathematician Joseph Petzval created a lens with an f/3.6 aperture, much faster than Chevalier lens that Daguerre had deployed. Combined, the advances reduced exposure time down to about a minute.

Albert Sands Southworth, daguerreotype, c. 1845-50

Josiah Johnson Hawes, daguerreotype, c. 1845-50

Antoine-François-Jean Claudet. Portrait of a Girl in Blue Dress, hand-colored daguerreotype, c. 1854

Despite the popularity of daguerreotype portraits, many extant examples remain unattributed to their makers. Among the known practitioners, few were as successful than Albert Sands Southworth and Josiah Johnson Hawes, working in Boston. Hawes brought his aesthetic sensibility as a portrait painter to the new medium while Southworth provided business acumen to maintain a steady flow of sitters.

Across the pond, Antoine-François-Jean Claudet ran a daguerreotype studio in London after learning the process directly from Daguerre. Claudet’s portraits were influential for the artist’s inclusion of painted backgrounds and accessories into his compositions. The addition of color would further the perceived naturalism of his work.

Travel views were another popular subject for adventurous daguerreotypists. Prior to photography, prints of destinations included in the Grand Tour were already desired by both the wealthy British travelers who had undertaken the journey across Europe as well as the “armchair” travelers at home. However, the status of the daguerreotype as a unique object posed logistical challenges for the commercial distribution of the images. Engravings based on daguerreotypes became a workaround for this problem. By leaning on the daguerreotype’s claim to truth, illustrations based on daguerreotypes were perceived as possessing an additional layer of fidelity to its subject. The introduction of the salted paper print would later change this industry by making it possible to create copies easily from negatives.

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey, Hexagonal Court, Temple of Jupiter, Baalbek, daguerreotype, 1843

Among the most awe-inspiring subjects captured by daguerreotypists was the moon. As soon as 1840, the scientist John Draper, working in New York, claimed the honor of producing the first photograph of the moon. However, it was a little over a decade later that John Adams Whipple would begin making a series of detailed images of the moon while working at Harvard University. Whipple, who was using the largest telescope in the world at the time, won the prize in photography for technical excellence at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Astronomical subjects and events would remain popular throughout the 19th century and beyond.

W. & F. Langenheim, Eclipse of the Sun, daguerreotype, 1854

The announcement of the daguerreotype was immediately followed by Henry Fox Talbot’s calotype. While Talbot’s invention profoundly changed the potential applications of photography by introducing the negative-positive process, daguerreotypes remained cherished for their remarkable detail. Today, workshops are occasionally held by the Penumbra Foundation, George Eastman House, and other locations, for those interested in learning how to create daguerreotypes.