Focus On: Alfred Stieglitz

First published here.

Alfred Stieglitz, The Terminal, 1893

An ambitious photographer, writer, and entrepreneur, Alfred Stieglitz had a tremendous impact on early 20th-Century art. Founder of the influential “291” gallery on Fifth Avenue, he played a leading role in the exposure of American audiences to European avant-garde painting and sculpture. His later curatorial efforts nurtured and tirelessly promoted the first distinctly American flavors of Modern art. A lifelong photographer, Stieglitz was instrumental in the push to elevate photography to the status of Art. His biography reveals an unflinching love of photography and art; his importance in the story of American art cannot be overstated.

Alfred Stieglitz, The Flatiron, 1903

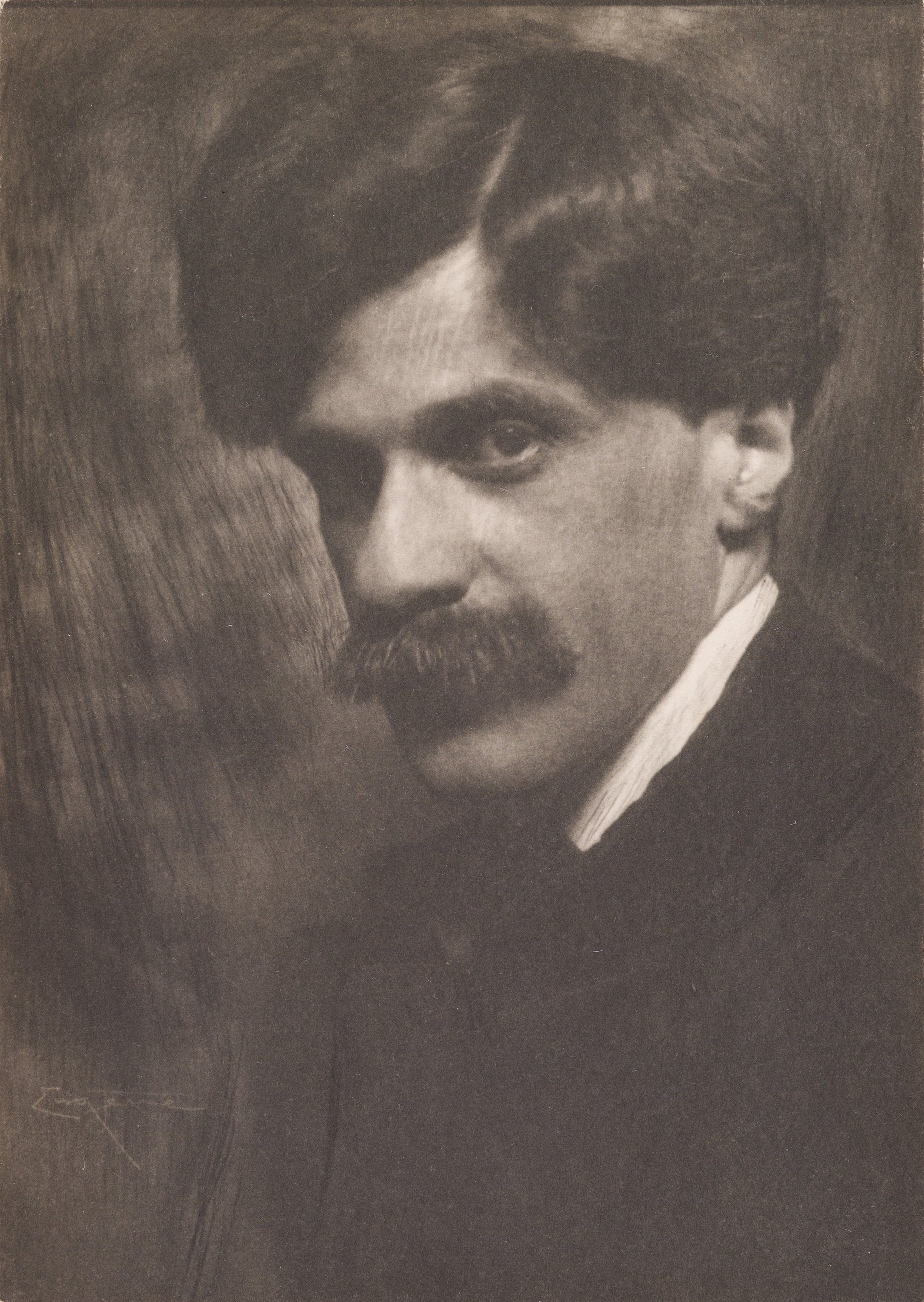

Frank Eugene, Alfred Stieglitz, 1907

Stieglitz was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, but spent the better part of his education in Germany, where he trained as a mechanical engineer. While abroad, he began taking photography seriously, entering his work in competitions and showing in magazines. In 1890, Stieglitz returned to America and began making a name for himself, first as an editor for The American Amateur Photographer, and later as an organizer of the Camera Club of New York. During his time with the Camera Club, Stieglitz used its publication, Camera Notes, to advance his ideas about photography. Influenced by members of the Linked Ring, whom he had befriended in London during a honeymoon-turned-professional-networking-tour in 1894, Stieglitz pushed for photographs to be viewed as objects capable of artistic and poetic expression.

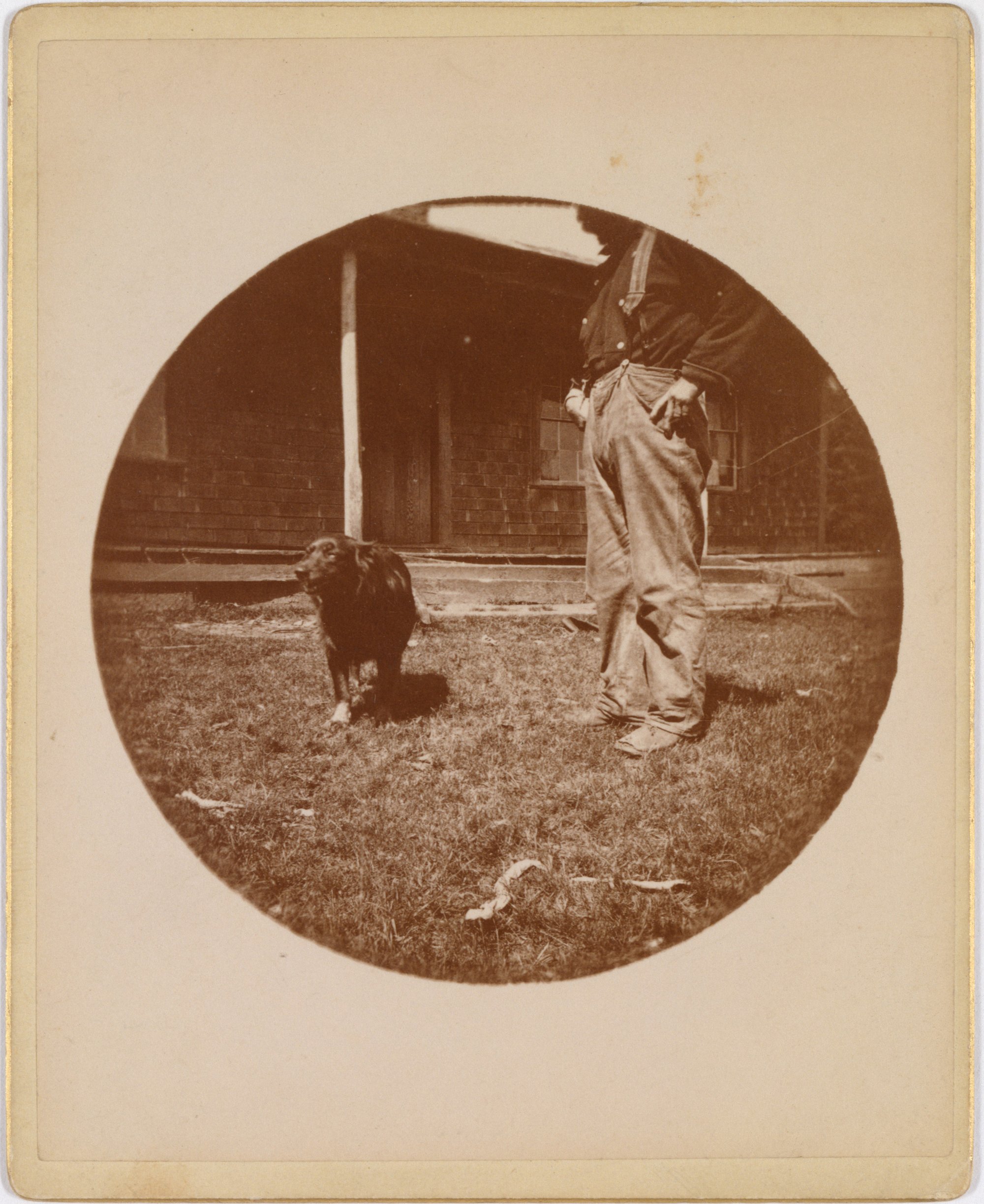

Anonymous, Dog and Man (Snapshot), c. 1890

Alfred Stieglitz, The City of Ambitions, 1910

The timing could not have been more pressing. About a decade earlier, two savvy businessmen in Rochester had formed a company that would transform the face of photography forever: The Eastman Dry Plate Company (later Eastman Kodak). In response to the proliferation of cameras, “easily operated by any school boy or girl,” Stieglitz set to work distinguishing his photographic vision from the snapshots of the unwashed masses:

“[I]n the photographic world today there are recognized but three classes of photographers—the ignorant, the purely technical, and the artistic. To the pursuit, the first bring nothing but what is not desirable; the second a purely technical education obtained after years of study; and the third bring the feeling and inspiration of the artist, to which is added afterward the purely technical knowledge. This class devote the best part of their lives to the work, and it is only after an intimate acquaintance with them and their productions that the casual observer comes to realize the fact that the ability to make a truly artistic photograph is not acquired off-hand, but is the result of an artistic instinct coupled with years of labor.”

Stieglitz resurrected Renaissance attitudes about artistic craft and genius and applied them to photography; satisfactory results were designated “Pictorial” photographs. In 1902, referencing earlier artist secessions in Munich and Vienna, he organized an exhibition of photographs under the title, “The Photo-Secession,” at the National Arts Club. The show aimed to defend Pictorial photography as a viable art form in response to the avalanche of poorly composed snaps, hackneyed clichés, and slapdash processing efforts tarnishing the medium.

Stieglitz, A Snapshot, Paris, 1911

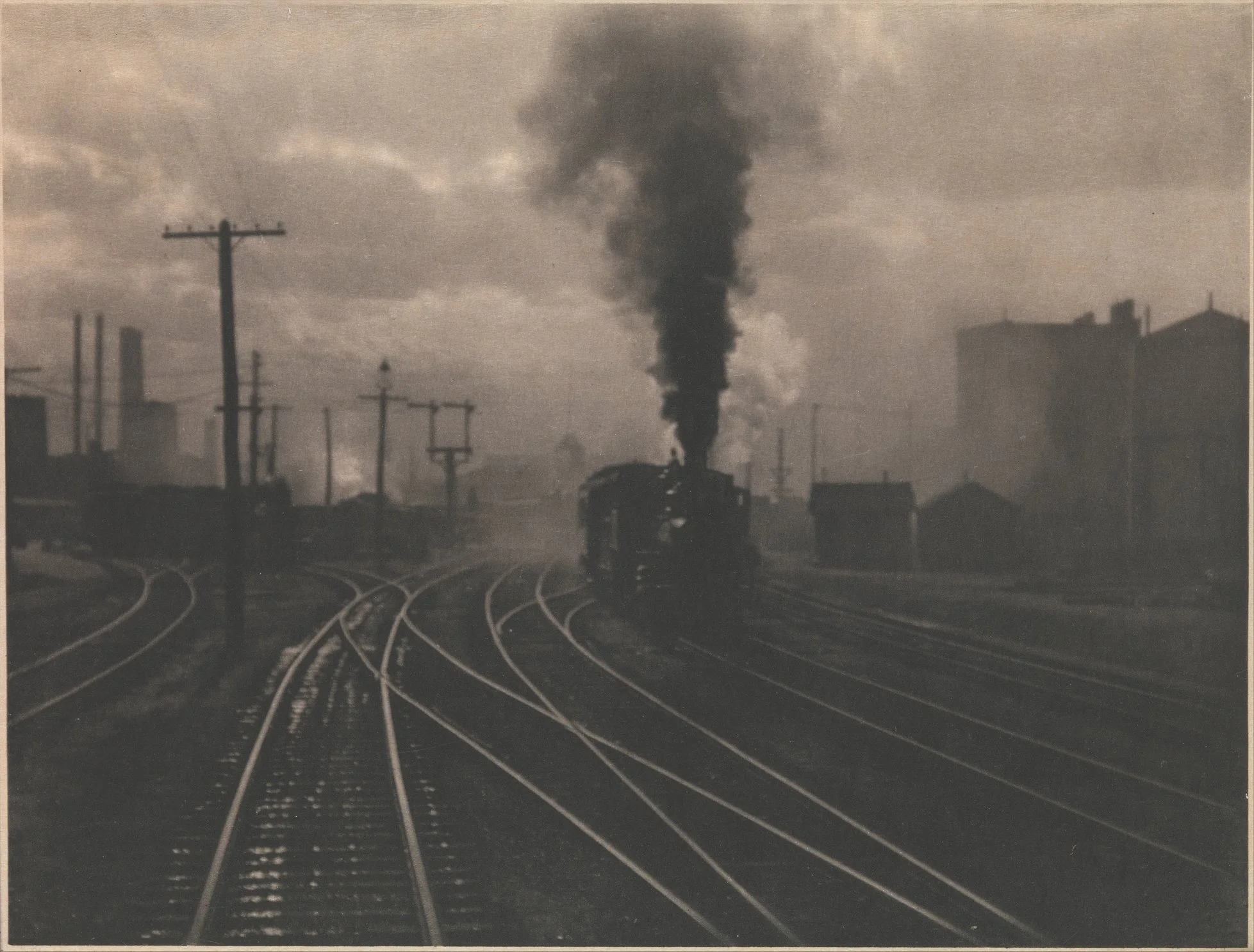

Alfred Stieglitz, The Hand of Man, 1902

After the show, Stieglitz left the Camera Club of New York and began a new publication, Camera Work, which became the aesthetic and theoretical touchstone of the Pictorialists. In 1905, Edward Steichen, a colleague and future curator of the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art, offered his studio as an exhibition space to Stieglitz, giving rise to the “Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession.” The space acted as a complement to the pages of Camera Work, allowing visitors to experience Pictorialist photography in a gallery setting.

Stieglitz’s early work reveals a keen awareness of European painting. Photographs such as The Hand of Man pay homage to the hazy aesthetic and urban fascination of the Impressionists (compare: Monet’s La gare Saint-Lazare, 1877). The use of photogravure and lush paper as means of presenting photographs in Camera Workfurther added to their visual and tactile appeal. Each issue was an indulgent undertaking, physically embodying the spirit of its maker. Stieglitz’s aesthetic evolved over time. The clean edges and sharp focus of his “straight” photographs stand in contrast to the sketchy style that first characterized the Pictorialists. Nevertheless, his commitment to the formal and expressive potential of the medium remained.

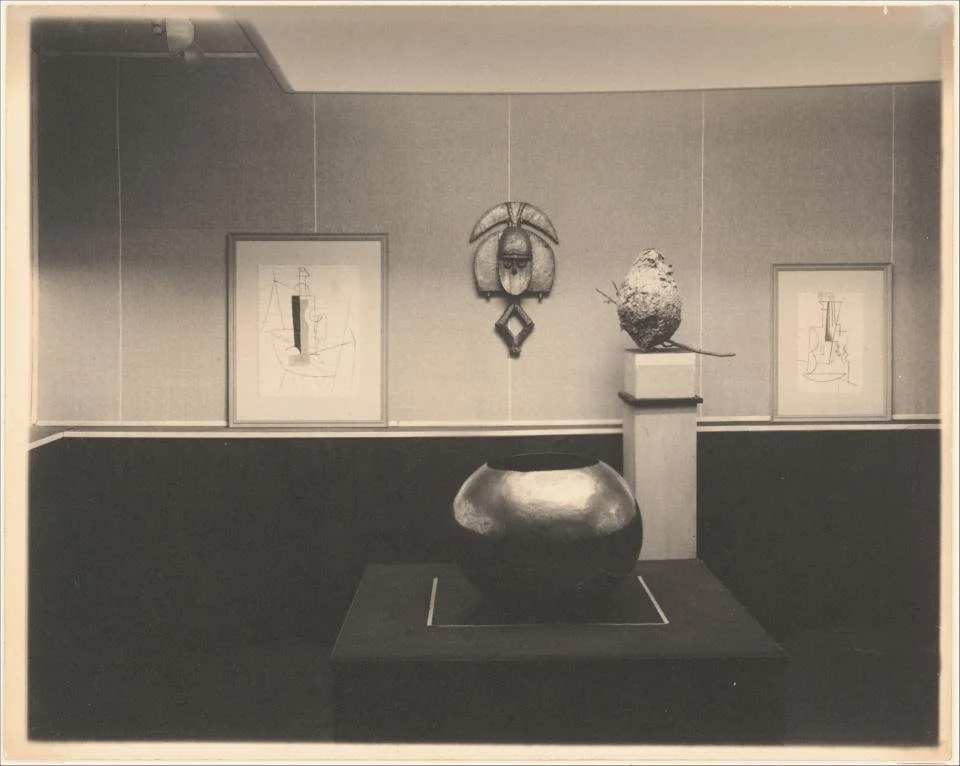

Alfred Stieglitz, "291—Picasso—Braque Exhibition," 1915

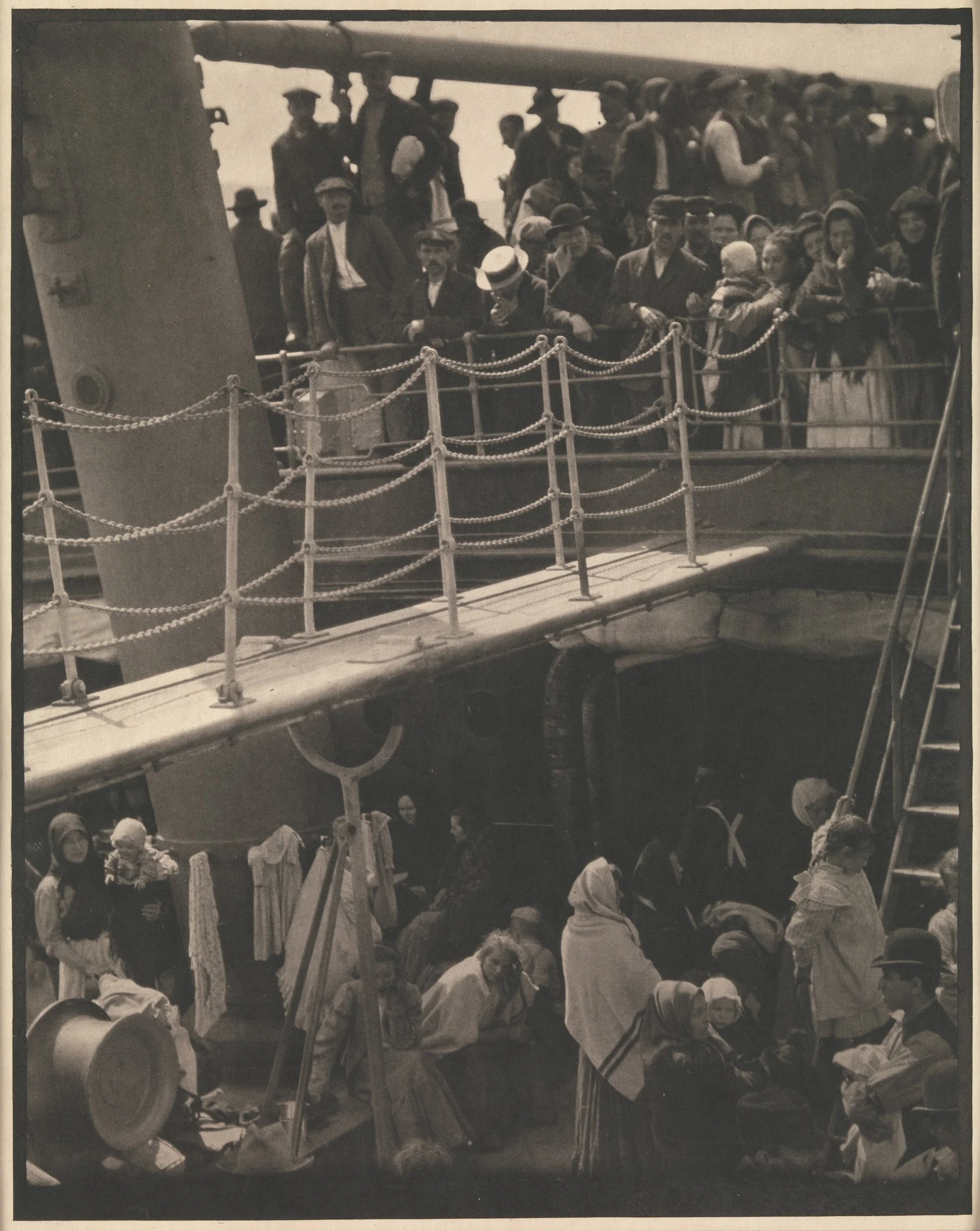

Stieglitz, The Steerage, 1907

Reflecting upon his iconic image, The Steerage, Stieglitz wrote:

"A round straw hat, the funnel leading out, the stairway leaning right, the white drawbridge with its railings made of circular chains—white suspenders crossing on the back of a man in the steerage below, round shapes of iron machinery, a mast cutting into the sky, making a triangular shape. I stood spellbound for a while, looking and looking. Could I photograph what I felt, looking and looking and still looking? I saw shapes related to each other. I saw a picture of shapes and underlying that the feeling I had about life.”

Despite its historical subject, the formal concerns expressed by Stieglitz share much more in common with contemporary avant-garde painting than documentary photography. Unsurprisingly, it was around this time that “The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession” was renamed 291, and Stieglitz began incrementally dedicating more space and time to presenting European painting and sculpture. The Steerage appeared in Camera Work for the first time in 1911, the same year that Stieglitz organized Picasso’s first solo show in America.

Alfred Stieglitz, Equivalent, 1925

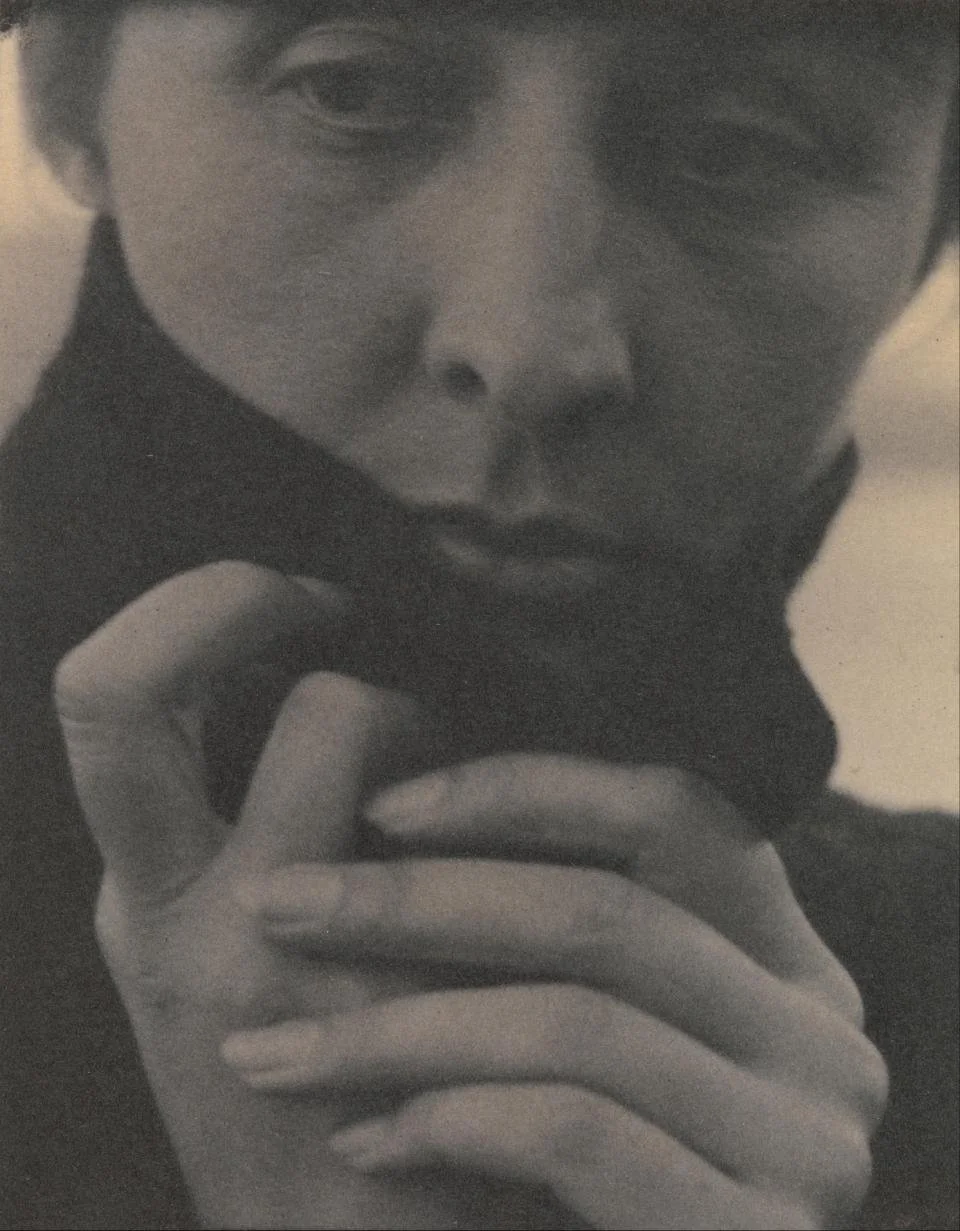

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918

In 1916, Stieglitz found a muse and future wife in the painter, Georgia O’Keeffe. Inspired by his new infatuation, his work began to take a figurative turn. Over the years, he created hundreds of photographs of O’Keeffe, whom he felt could not be adequately represented in a single image.

Stieglitz took an equally exhaustive approach to a subject in his later image series of clouds, Equivalents. Echoing the obsessive repetition seen in Monet’s water lilies or Cezanne’s landscape views, the series expresses a deep fascination with the play of light and shadow in the sky. Although he continued to take photographs throughout the rest of his life, the bulk of Stieglitz’s later years were devoted to championing the work shown in his galleries.